---

title: "Using word embeddings"

output:

html_notebook:

theme: cerulean

highlight: textmate

---

```{r setup, include=FALSE}

knitr::opts_chunk$set(warning = FALSE, message = FALSE)

```

***

This notebook contains the second code sample found in Chapter 6, Section 1 of [Deep Learning with R](https://www.manning.com/books/deep-learning-with-r). Note that the original text features far more content, in particular further explanations and figures: in this notebook, you will only find source code and related comments.

***

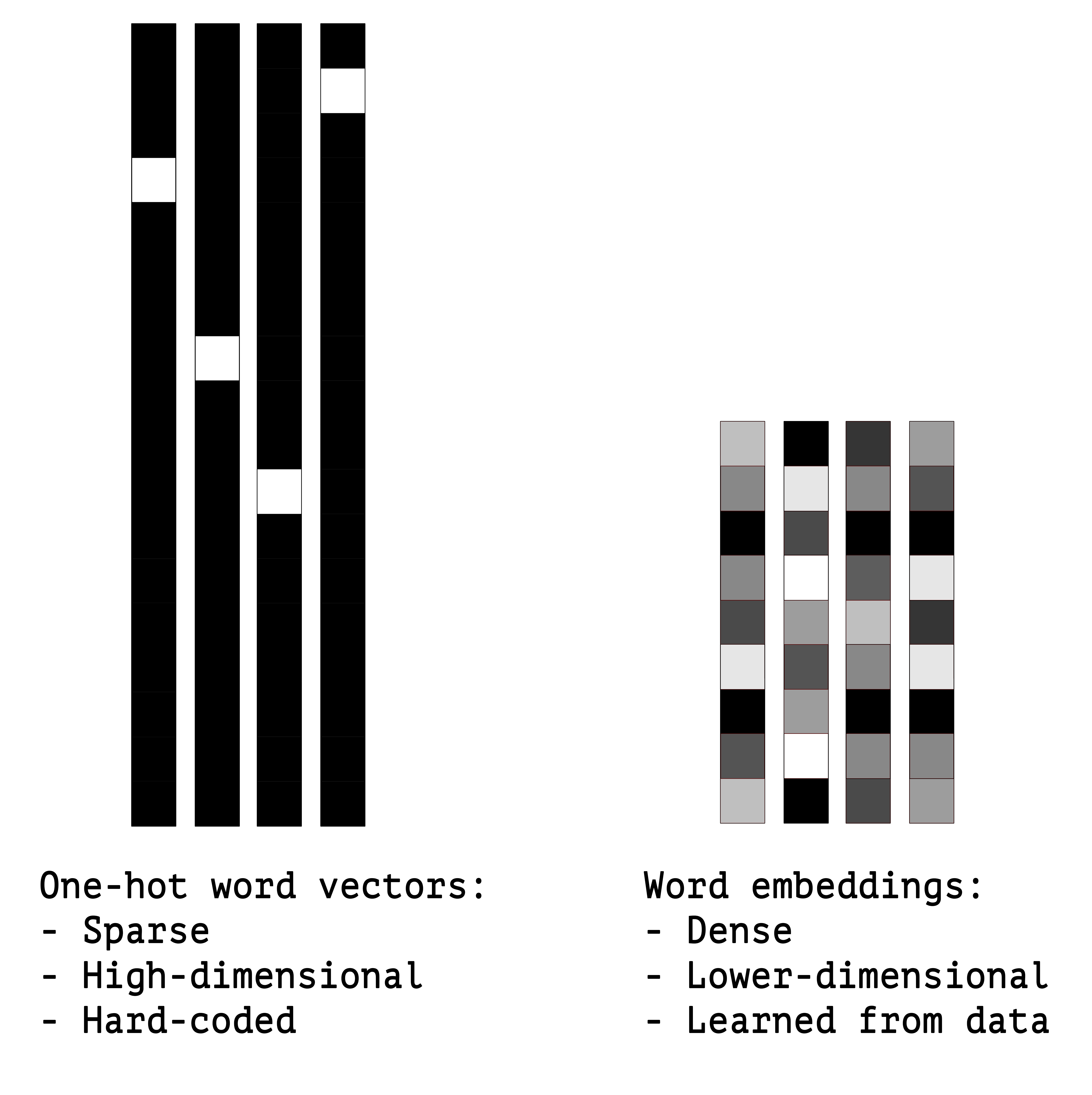

Another popular and powerful way to associate a vector with a word is the use of dense "word vectors", also called "word embeddings". While the vectors obtained through one-hot encoding are binary, sparse (mostly made of zeros) and very high-dimensional (same dimensionality as the number of words in the vocabulary), "word embeddings" are low-dimensional floating point vectors (i.e. "dense" vectors, as opposed to sparse vectors). Unlike word vectors obtained via one-hot encoding, word embeddings are learned from data. It is common to see word embeddings that are 256-dimensional, 512-dimensional, or 1024-dimensional when dealing with very large vocabularies. On the other hand, one-hot encoding words generally leads to vectors that are 20,000-dimensional or higher (capturing a vocabulary of 20,000

token in this case). So, word embeddings pack more information into far fewer dimensions.

There are two ways to obtain word embeddings:

* Learn word embeddings jointly with the main task you care about (e.g. document classification or sentiment prediction). In this setup, you would start with random word vectors, then learn your word vectors in the same way that you learn the weights of a neural network.

* Load into your model word embeddings that were pre-computed using a different machine learning task than the one you are trying to solve. These are called "pre-trained word embeddings".

Let's take a look at both.

## Learning word embeddings with an embedding layer

The simplest way to associate a dense vector to a word would be to pick the vector at random. The problem with this approach is that the resulting embedding space would have no structure: for instance, the words "accurate" and "exact" may end up with completely different embeddings, even though they are interchangeable in most sentences. It would be very difficult for a deep neural network to make sense of such a noisy, unstructured embedding space.

To get a bit more abstract: the geometric relationships between word vectors should reflect the semantic relationships between these words. Word embeddings are meant to map human language into a geometric space. For instance, in a reasonable embedding space, we would expect synonyms to be embedded into similar word vectors, and in general we would expect the geometric distance (e.g. L2 distance) between any two word vectors to relate to the semantic distance of the associated words (words meaning very different things would be embedded to points far away from each other, while related words would be closer). Even beyond mere distance, we may want specific __directions__ in the embedding space to be meaningful.

In real-world word embedding spaces, common examples of meaningful geometric transformations are "gender vectors" and "plural vector". For instance, by adding a "female vector" to the vector "king", one obtain the vector "queen". By adding a "plural vector", one obtain "kings". Word embedding spaces typically feature thousands of such interpretable and potentially useful vectors.

Is there some "ideal" word embedding space that would perfectly map human language and could be used for any natural language processing task? Possibly, but in any case, we have yet to compute anything of the sort. Also, there isn't such a thing as "human language", there are many different languages and they are not isomorphic, as a language is the reflection of a specific culture and a specific context. But more pragmatically, what makes a good word embedding space depends heavily on your task: the perfect word embedding space for an English-language movie review sentiment analysis model may look very different from the perfect embedding space for an English-language legal document classification model, because the importance of certain semantic relationships varies from task to task.

It's thus reasonable to _learn_ a new embedding space with every new task. Fortunately, backpropagation makes this easy, and Keras makes it

even easier. It's about learning the weights of a layer using `layer_embedding()`

```{r}

library(keras)

# The embedding layer takes at least two arguments:

# the number of possible tokens, here 1000 (1 + maximum word index),

# and the dimensionality of the embeddings, here 64.

embedding_layer <- layer_embedding(input_dim = 1000, output_dim = 64)

```

A `layer_embedding()` is best understood as a dictionary that maps integer indices (which stand for specific words) to dense vectors. It takes integers as input, it looks up these integers in an internal dictionary, and it returns the associated vectors. It's effectively a dictionary lookup (see figure 6.4).

An embedding layer takes as input a 2D tensor of integers, of shape `(samples, sequence_length)`, where each entry is a sequence of integers. It can embed sequences of variable lengths: for instance, you could feed into the embedding layer in the previous example batches with shapes `(32, 10)` (batch of 32 sequences of length 10) or `(64, 15)` (batch of 64 sequences of length 15). All sequences in a batch must have the same length, though (because you need to pack them into a single tensor), so sequences that are shorter than others should be padded with zeros, and sequences that are longer should be truncated.

This layer returns a 3D floating-point tensor, of shape `(samples, sequence_length, embedding_dimensionality)`. Such a 3D tensor can then be processed by an RNN layer or a 1D convolution layer (both will be introduced in the following sections).

When you instantiate an embedding layer, its weights (its internal dictionary of token vectors) are initially random, just as with any other layer. During training, these word vectors are gradually adjusted via backpropagation, structuring the space into something the downstream model can exploit. Once fully trained, the embedding space will show a lot of structure -- a kind of structure specialized for the specific problem for which you were training your model.

Let's apply this idea to the IMDB movie-review sentiment-prediction task that you're already familiar with. First, you'll quickly prepare the data. You'll restrict the movie reviews to the top 10,000 most common words (as you did the first time you worked with this dataset) and cut off the reviews after only 20 words. The network will learn 8-dimensional embeddings for each of the 10,000 words, turn the input integer sequences (2D integer tensor) into embedded sequences (3D float tensor), flatten the tensor to 2D, and train a single dense layer on top for classification.

```{r}

# Number of words to consider as features

max_features <- 10000

# Cut texts after this number of words

# (among top max_features most common words)

maxlen <- 20

# Load the data as lists of integers.

imdb <- dataset_imdb(num_words = max_features)

c(c(x_train, y_train), c(x_test, y_test)) %<-% imdb

# This turns our lists of integers

# into a 2D integer tensor of shape `(samples, maxlen)`

x_train <- pad_sequences(x_train, maxlen = maxlen)

x_test <- pad_sequences(x_test, maxlen = maxlen)

```

```{r, echo=TRUE, results='hide'}

model <- keras_model_sequential() %>%

# We specify the maximum input length to our Embedding layer

# so we can later flatten the embedded inputs

layer_embedding(input_dim = 10000, output_dim = 8,

input_length = maxlen) %>%

# We flatten the 3D tensor of embeddings

# into a 2D tensor of shape `(samples, maxlen * 8)`

layer_flatten() %>%

# We add the classifier on top

layer_dense(units = 1, activation = "sigmoid")

model %>% compile(

optimizer = "rmsprop",

loss = "binary_crossentropy",

metrics = c("acc")

)

history <- model %>% fit(

x_train, y_train,

epochs = 10,

batch_size = 32,

validation_split = 0.2

)

```

We get to a validation accuracy of ~75%, which is pretty good considering that we only look at 20 words from each review. But note that merely flattening the embedded sequences and training a single dense layer on top leads to a model that treats each word in the input sequence separately, without considering inter-word relationships and structure sentence (e.g. it would likely treat both _"this movie is shit"_ and _"this movie is the shit"_ as being negative "reviews"). It would be much better to add recurrent layers or 1D convolutional layers on top of the embedded sequences to learn features that take into account each sequenceas a whole. That's what we will focus on in the next few sections.

## Using pre-trained word embeddings

Sometimes, you have so little training data available that could never use your data alone to learn an appropriate task-specific embedding of your vocabulary. What to do then?

Instead of learning word embeddings jointly with the problem you want to solve, you could be loading embedding vectors from a pre-computed embedding space known to be highly structured and to exhibit useful properties -- that captures generic aspects of language structure. The rationale behind using pre-trained word embeddings in natural language processing is very much the same as for using pre-trained convnets in image classification: we don't have enough data available to learn truly powerful features on our own, but we expect the features that we need to be fairly generic, i.e. common visual features or semantic features. In this case it makes sense to reuse features learned on a different problem.

Such word embeddings are generally computed using word occurrence statistics (observations about what words co-occur in sentences or documents), using a variety of techniques, some involving neural networks, others not. The idea of a dense, low-dimensional embedding space for words, computed in an unsupervised way, was initially explored by Bengio et al. in the early 2000s, but it only started really taking off in research and industry applications after the release of one of the most famous and successful word embedding scheme: the Word2Vec algorithm, developed by Mikolov at Google in 2013. Word2Vec dimensions capture specific semantic properties, e.g. gender.

There are various pre-computed databases of word embeddings that can download and start using in a Keras embedding layer. Word2Vec is one of them. Another popular one is called "GloVe", developed by Stanford researchers in 2014. It stands for "Global Vectors for Word Representation", and it is an embedding technique based on factorizing a matrix of word co-occurrence statistics. Its developers have made available pre-computed embeddings for millions of English tokens, obtained from Wikipedia data or from Common Crawl data.

Let's take a look at how you can get started using GloVe embeddings in a Keras model. The same method will of course be valid for Word2Vec embeddings or any other word embedding database that you can download. We will also use this example to refresh the text tokenization techniques we introduced a few paragraphs ago: we will start from raw text, and work our way up.

## Putting it all together: from raw text to word embeddings

We will be using a model similar to the one we just went over -- embedding sentences in sequences of vectors, flattening them and training a

dense layer on top. But we will do it using pre-trained word embeddings, and instead of using the pre-tokenized IMDB data packaged in

Keras, we will start from scratch, by downloading the original text data.

### Download the IMDB data as raw text

First, head to http://ai.stanford.edu/~amaas/data/sentiment and download the raw IMDB dataset (if the URL isn't working anymore, Google "IMDB dataset"). Uncompress it.

Now, let's collect the individual training reviews into a list of strings, one string per review. You'll also collect the review labels (positive / negative) into a `labels` list.

```{r}

imdb_dir <- "~/Downloads/aclImdb"

train_dir <- file.path(imdb_dir, "train")

labels <- c()

texts <- c()

for (label_type in c("neg", "pos")) {

label <- switch(label_type, neg = 0, pos = 1)

dir_name <- file.path(train_dir, label_type)

for (fname in list.files(dir_name, pattern = glob2rx("*.txt"),

full.names = TRUE)) {

texts <- c(texts, readChar(fname, file.info(fname)$size))

labels <- c(labels, label)

}

}

```

### Tokenize the data

Let's vectorize the texts we collected, and prepare a training and validation split. We will merely be using the concepts we introduced earlier in this section.

Because pre-trained word embeddings are meant to be particularly useful on problems where little training data is available (otherwise, task-specific embeddings are likely to outperform them), we will add the following twist: we restrict the training data to its first 200 samples. So we will be learning to classify movie reviews after looking at just 200 examples...

```{r}

library(keras)

maxlen <- 100 # We will cut reviews after 100 words

training_samples <- 200 # We will be training on 200 samples

validation_samples <- 10000 # We will be validating on 10000 samples

max_words <- 10000 # We will only consider the top 10,000 words in the dataset

tokenizer <- text_tokenizer(num_words = max_words) %>%

fit_text_tokenizer(texts)

sequences <- texts_to_sequences(tokenizer, texts)

word_index = tokenizer$word_index

cat("Found", length(word_index), "unique tokens.\n")

data <- pad_sequences(sequences, maxlen = maxlen)

labels <- as.array(labels)

cat("Shape of data tensor:", dim(data), "\n")

cat('Shape of label tensor:', dim(labels), "\n")

# Split the data into a training set and a validation set

# But first, shuffle the data, since we started from data

# where sample are ordered (all negative first, then all positive).

indices <- sample(1:nrow(data))

training_indices <- indices[1:training_samples]

validation_indices <- indices[(training_samples + 1):

(training_samples + validation_samples)]

x_train <- data[training_indices,]

y_train <- labels[training_indices]

x_val <- data[validation_indices,]

y_val <- labels[validation_indices]

```

### Download the GloVe word embeddings

Head to https://nlp.stanford.edu/projects/glove/ (where you can learn more about the GloVe algorithm), and download the pre-computed embeddings from 2014 English Wikipedia. It's a 822MB zip file named `glove.6B.zip`, containing 100-dimensional embedding vectors for 400,000 words (or non-word tokens). Un-zip it.

### Pre-process the embeddings

Let's parse the un-zipped file (it's a `txt` file) to build an index mapping words (as strings) to their vector representation (as number

vectors).

```{r}

glove_dir = '~/Downloads/glove.6B'

lines <- readLines(file.path(glove_dir, "glove.6B.100d.txt"))

embeddings_index <- new.env(hash = TRUE, parent = emptyenv())

for (i in 1:length(lines)) {

line <- lines[[i]]

values <- strsplit(line, " ")[[1]]

word <- values[[1]]

embeddings_index[[word]] <- as.double(values[-1])

}

cat("Found", length(embeddings_index), "word vectors.\n")

```

Next, you'll build an embedding matrix that you can load into an embedding layer. It must be a matrix of shape `(max_words, embedding_dim)`, where each entry _i_ contains the `embedding_dim`-dimensional vector for the word of index _i_ in the reference word index (built during tokenization). Note that index 1 isn't supposed to stand for any word or token -- it's a placeholder.

```{r}

embedding_dim <- 100

embedding_matrix <- array(0, c(max_words, embedding_dim))

for (word in names(word_index)) {

index <- word_index[[word]]

if (index < max_words) {

embedding_vector <- embeddings_index[[word]]

if (!is.null(embedding_vector))

# Words not found in the embedding index will be all zeros.

embedding_matrix[index+1,] <- embedding_vector

}

}

```

### Define a model

We will be using the same model architecture as before:

```{r}

model <- keras_model_sequential() %>%

layer_embedding(input_dim = max_words, output_dim = embedding_dim,

input_length = maxlen) %>%

layer_flatten() %>%

layer_dense(units = 32, activation = "relu") %>%

layer_dense(units = 1, activation = "sigmoid")

summary(model)

```

### Load the GloVe embeddings in the model

The embedding layer has a single weight matrix: a 2D float matrix where each entry _i_ is the word vector meant to be associated with index _i_. Simple enough. Load the GloVe matrix you prepared into the embedding layer, the first layer in the model.

```{r}

get_layer(model, index = 1) %>%

set_weights(list(embedding_matrix)) %>%

freeze_weights()

```

Additionally, you'll freeze the weights of the embedding layer, following the same rationale you're already familiar with in the context of pretrained convnet features: when parts of a model are pretrained (like your embedding layer) and parts are randomly initialized (like your classifier), the pretrained parts shouldn't be updated during training, to avoid forgetting what they already know. The large gradient updates triggered by the randomly initialized layers would be disruptive to the already-learned features.

### Train and evaluate

Let's compile our model and train it:

```{r, echo=TRUE, results='hide'}

model %>% compile(

optimizer = "rmsprop",

loss = "binary_crossentropy",

metrics = c("acc")

)

history <- model %>% fit(

x_train, y_train,

epochs = 20,

batch_size = 32,

validation_data = list(x_val, y_val)

)

save_model_weights_hdf5(model, "pre_trained_glove_model.h5")

```

Let's plot its performance over time:

```{r}

plot(history)

```

The model quickly starts overfitting, unsurprisingly given the small number of training samples. Validation accuracyhas high variance for the same reason, but seems to reach high 50s.

Note that your mileage may vary: since we have so few training samples, performance is heavily dependent on which exact 200 samples we picked, and we picked them at random. If it worked really poorly for you, try picking different random set of 200 samples, just for the sake of the exercise (in real life you don't get to pick your training data).

We can also try to train the same model without loading the pre-trained word embeddings and without freezing the embedding layer. In that case, we would be learning a task-specific embedding of our input tokens, which is generally more powerful than pre-trained word embeddings when lots of data is available. However, in our case, we have only 200 training samples. Let's try it:

```{r, echo=TRUE, results='hide'}

model <- keras_model_sequential() %>%

layer_embedding(input_dim = max_words, output_dim = embedding_dim,

input_length = maxlen) %>%

layer_flatten() %>%

layer_dense(units = 32, activation = "relu") %>%

layer_dense(units = 1, activation = "sigmoid")

model %>% compile(

optimizer = "rmsprop",

loss = "binary_crossentropy",

metrics = c("acc")

)

history <- model %>% fit(

x_train, y_train,

epochs = 20,

batch_size = 32,

validation_data = list(x_val, y_val)

)

```

```{r}

plot(history)

```

Validation accuracy stalls in the low 50s. So in our case, pre-trained word embeddings does outperform jointly learned embeddings. If you increase the number of training samples, this will quickly stop being the case -- try it as an exercise.

Finally, let's evaluate the model on the test data. First, we will need to tokenize the test data:

```{r}

test_dir <- file.path(imdb_dir, "test")

labels <- c()

texts <- c()

for (label_type in c("neg", "pos")) {

label <- switch(label_type, neg = 0, pos = 1)

dir_name <- file.path(test_dir, label_type)

for (fname in list.files(dir_name, pattern = glob2rx("*.txt"),

full.names = TRUE)) {

texts <- c(texts, readChar(fname, file.info(fname)$size))

labels <- c(labels, label)

}

}

sequences <- texts_to_sequences(tokenizer, texts)

x_test <- pad_sequences(sequences, maxlen = maxlen)

y_test <- as.array(labels)

```

And let's load and evaluate the first model:

```{r}

model %>%

load_model_weights_hdf5("pre_trained_glove_model.h5") %>%

evaluate(x_test, y_test, verbose = 0)

```

We get an appalling test accuracy of 56%. Working with just a handful of training samples is hard!